Originally published in the Washington Post’s series Under God

I went to speak with Eisenman last week mostly because I wanted to hear from one of the brilliant architects of our time. But I also wanted to learn if and how he felt architecture could negotiate competing political, religious, and historical forces in a way that enriches our world rather than dividing us. Eisenman wrestled one of the great works of contemporary architecture from the Holocaust, so I assumed that perhaps he had ideas on how to transcend our current cultural and political dramas.

ME: How do you approach the Holocaust as something that can be in any way represented, or is that even something you were after? How do you tackle such a loaded topic via architecture?

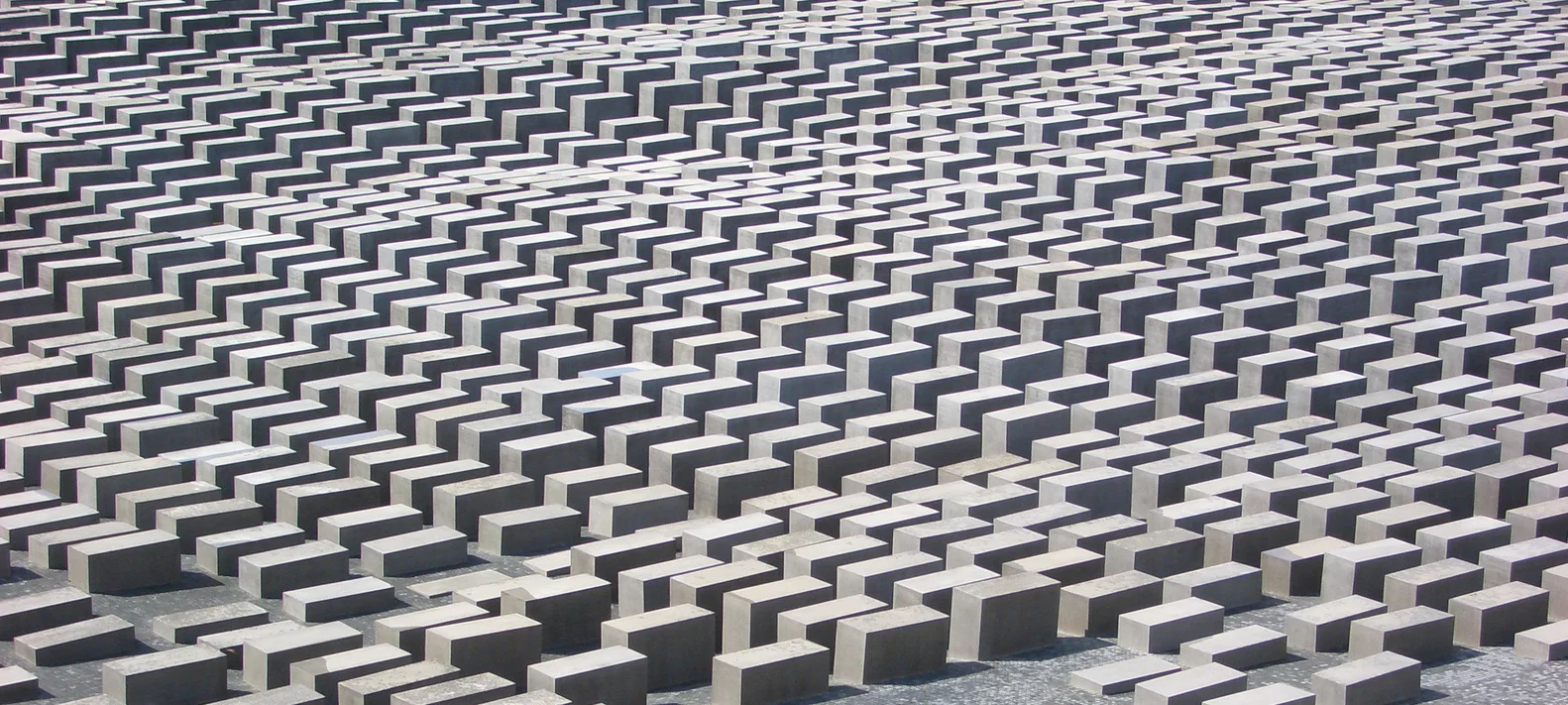

PE: Well, it’s not an easy question because I had to tackle it architecturally. I think most attempts at architecture have not been, for me, successful. They tend to be nostalgic for this awful event. You cannot memorialize this action. And so the field of silence, basically, doesn’t say anything. It has no direction, it has no meaning, it has no, no nothing, it’s just a field of pillars that stands mute in the Berlin context.

I think when one considers the Holocaust, as far as I’m concerned, silence is more appropriate than speaking. And when architecture tries to speak it becomes mock-ish, sentimental, and banal.

Everybody says, well, what does this mean? It doesn’t mean anything; it is. And it is there to experience its being, and being of being there. But basically that is it.

ME: Architecture of this sort doesn’t exist, as far as I have seen…

PE: A lot of people have told me how moved they’ve been by it, and I appreciate that, I think we were, we hit it, we were lucky. I feel that enough people have, in their own way, whether they jump up on the pillars, or play tag, or make love, or whatever, they all seem to feel something about it that’s different. There’s a difference between making a memorial and the camps themselves — the memorial is not the place where it all took place, so it’s something other. It has a distance from the camps. When it becomes integrated into the daily being of Berliners. I think that makes it a success. You know? Meet me at the Holocaust memorial. Or I’m going to a field trip at the Holocaust memorial. Now at least 3 million people per year say that to someone else.

ME: So it’s just of the world? What I’ve been thinking through is how people tend to map their own ideas to architectural projects…

PE: They always will. They do map, people map it to anything

ME: For me it produces a sort of atmospheric experience, I don’t know where it lands.

PE: No, you don’t need to know. But you can’t ask me to explain to you what feelings that you have. I’m the last person who can say to you how we did it, because I don’t know.